How Historical Inequities Shape the Course of Pandemics

By

Nadja Durbach

PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

Gregory Smoak

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

AND DIRECTOR OF THE AMERICAN WEST CENTER

We can never view pandemics as purely biological events. While it is true that microbes are discrete organisms, replicating and mutating through natural processes beyond our control, human actions and power structures have always shaped the epidemics those pathogens have spawned. This is as true today as it was when relentless waves of disease first began to devastate Native peoples in the centuries following European contact. Native peoples were subject to dozens of distinct epidemics that included bubonic plague, measles, typhus, influenza, and smallpox. Pre-contact

Above Left: Sixteenth-century Aztec

drawings of smallpox and measles

victims

Below: Nurses working in the Red

Cross rooms in Seattle, WA, with

influenza masks on faces, 1918

▼

was marked by warfare, social dislocation, slave raiding, and the destruction of Native

subsistence bases. Malnutrition was in fact the single greatest factor in spiking

epidemic mortality rates. The kind of health care infrastructure that we may take

for granted today did not exist; caring for the afflicted was the responsibility of

kin and community. Regardless of biological immunity, any society in collapse, unable

to feed or heal itself, stands little chance in the face of a pandemic. Still, generations

of Euro-Americans cited high Native mortality rates as evidence of inherent Native

weakness, displacing blame.

Native peoples were not the only Americans subject to racist discourses and actions

that shaped their experience of epidemic disease. When yellow fever hit Philadelphia

in 1793, esteemed doctor Benjamin Rush, one of the signatories of the Declaration

of Independence, theorized that African Americans were immune to the disease. While much

of Philadelphia’s white population attempted to self-quarantine, its free Black people

were

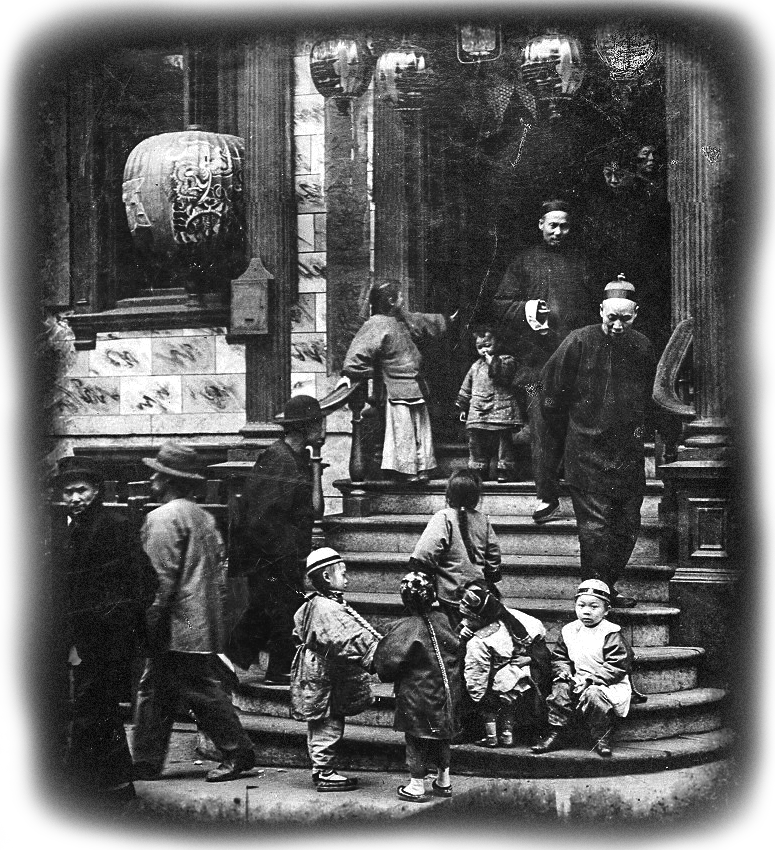

Above: San Francisco's Chinatown c. 1900. Photo by Arnold Genthe

Below: Black people struck by the Spanish Flu of 1918 received substandard care in segregated

hospitals.

▼

recruited to be first responders: they were put to work as nurses, coffin makers,

and grave diggers, coming into direct contact with contagious bodies. While at least

240 African Americans died of the disease, debunking Rush’s theory, they were nevertheless

accused of profiteering and looting rather than being praised for doing the dangerous

work of caring for the sick and the dead.

Since the early 19th century, immigrants to the United States whose “whiteness” was

always contested, have also been blamed for pandemic diseases. In the 1830s and 40s,

when they arrived in America seeking economic opportunity and fleeing devastating

famine, the Irish—considered both racially inferior and as Catholics widely despised

by the majority Protestant population —were accused of spreading cholera. The Jewish

refugees from Eastern Europe who passed through Ellis Island around the turn of the

century

in the wake of anti-Semitic programs

During the last great global pandemic —the influenza of 1918-1919—worldwide, some half a billion people were infected and up to 50 million died. In the United States,

Native peoples were hit harder than any other population. Nearly one quarter of all

people living on reservations came down with influenza between October 1918 and March

1919, and 9 percent died. That was quadruple the death rate in America’s largest cities.

The influenza of 1918 was particularly devastating for the Navajo people. An estimated

40 percent fell ill and at least 2,000 Navajos out of a population of just over 30,000

died. Rather than blaming preexisting conditions, malnutrition, and lack of adequate

health care for the mortality rate, many physicians, scientists, and government officials

interpreted the death toll as evidence of the genetic inferiority and bodily weakness

of a “primitive race.”

It is no surprise to historians that this

novel virus is now ravaging the United States’ least privileged and most vulnerable communities. In 2020, the Navajo Nation is again at the center of this pandemic. Some 175,000 people currently live on the Navajo Nation, an area the size of West Virginia, whose infection rate is nevertheless almost double that of New York state. Many of the same circumstances that spiked Navajo morbidity and mortality a century ago are still factors today. Preexisting conditions such as diabetes and heart disease and limited access to health care have made COVID-19 a deadly threat to this community in particular and reveal how historical inequities continue to shape the course of pandemics. Like the African Americans that Rush conscripted as first

At the same time as we invest in containing the spread of this virus... we should thus attend to the lessons of the past.

The Navajo Monument Valley Tribal Park in Oljato-Monument Valley, UT, closed to the

public in an effort to prevent the spread of COVID-19 on the Navajo reservation (source)

▼